A representative sample of anything is an unbiased selection from the whole population. It’s a statistical concept that applies to everything from opinion polls to laboratory testing. In principle it applies to concrete- and mortar testing as well.

Sampling fresh concrete

It’s fairly easy to get a representative sample of fresh concrete. ASTM C172 requires the sample to be a composite of two or more portions from the middle 80% of the load. Each portion must be from the entire discharge stream. Once you have all the portions, you mix them well and take what you need for your tests.

Sampling hardened concrete

However, getting a statistically valid representative sample of hardened concrete means taking lots of cores. Even if the budget allows for that much coring and testing, owners don’t want all those holes in their structures. That means you’ll end up with far fewer cores than you need for a truly representative sample.

So can you still get something meaningful? Yes, if you’re judicious about where and how you select the core locations. That’s part of your overall strategy for the investigation.

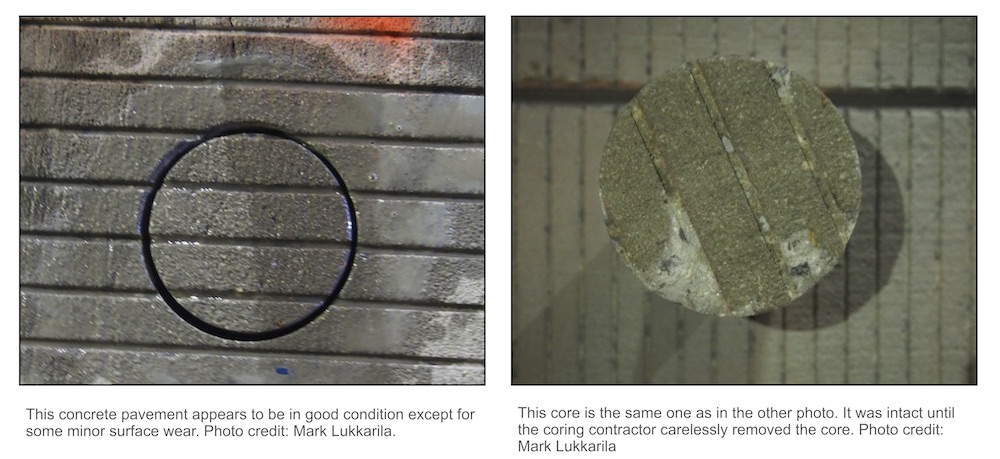

Instead of taking a representative sample of locations throughout the structure, you use visual examination and nondestructive testing to home in on what kinds of tests you need to do and where you need to take cores. If you’re verifying the in-place strength, you need a set of three cores for every test. If you’re diagnosing scaled concrete flatwork, you want cores in which the surface is about to scale off.

You may be able to use the same core for more than one test. It’s often possible to conduct a petrographic examination of one half of a core and chemical analysis of the other half, for example. And you can use a light microscope and an electron microscope on the same thin section.

What about fractured samples? Can you just take a piece that’s broken off, or use a hammer and chisel to break off a piece? This kind of sample is almost guaranteed to be useless. It’s very likely to be contaminated with whatever it’s come into contact with. And it’s the least representative sample you can get, as it’s broken off at the weakest point.

Sampling masonry mortar

Sometimes clients need to replicate an existing mortar, for example, for repairs to a historic structure. In that case it’s not enough to formulate a new mortar of the same color. The new mortar must be compatible with the old mortar and the brick or stone it holds together.

Masonry expands on heating and contracts on cooling. The mortar will also swell on wetting and shrink on drying. If the mortar is too strong or stiff, when its volume changes it will tear apart brick and softer stones such as our local limestone.

To get all the properties right, the petrographer needs more information than can be had from a small sample of mortar broken off from the wall. Ideally, you’ll provide a hand-size sample in one piece. That way the petrographer can see the porosity, identify the inclusions present, and take a representative sample for chemical analysis.

Also, if the masonry has undergone tuckpointing, make sure the mortar sample is from the original mortar and not from the repair.